Establishing the review & what was achieved

The renaming of some of Hackney shared spaces was a direct response to the summer of 2020 when Black Lives Matter was galvanised in response to the [racial] inequalities evidence by the Covid-19 pandemic, the international response to the death of George Floyd and the dramatic removal of a long contested statue of an English slave owner.

This series of blogs shares how Hackney Council responded to this context and resident’s calls to action; from the formation of Review, Rename Reclaim and its achievements, the Hackney Naming Hub and use of inclusive naming for new housing developments.

Mayor of Hackney, Philip Glanville holding a Black Lives Matter placard, in 2020.

In the summer of 2020, the Government Covid-19 report, set out evidence that the pandemic was disproportionately affecting people from Black and Asian backgrounds, as well as those with other protected characteristics under the equalities act.

This news had followed the murder of African-American, George Floyd, by police officers in the US that galvanised an international Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, first seen in 2016.

In the UK, alongside BLM demonstrations of solidarity, the Robert Colston statue in Bristol was forcibly removed from its plinth by campaigners. This was quickly followed by the quiet removal of Robert Milligan’s statue by the Canal & River Trust in the neighbouring London Borough of Tower Hamlets.

This context led Hackney Council to launch its own review into place names and memorials, which was to become foundational to the council’s anti-racist strategy developed in response to Hackney Council’s Black Lives Matter motion, passed in July 2020.

Establishing the review

The Review was established to understand the presence of racist histories across Hackney’s public realm in recognition that the racist structures created to support the historic practices of African enslavement and its profiteering (1660-1848) and imperialism in British colonies remain present in contemporary society as Afrophobia and systemic racism. Where possible removing names would be supported, alongside the introduction of more representative naming.

Review, Rename & Reclaim was supported by a community steering panel of African-heritage elders, academics and campaigners, alongside educationalists, to support Hackney Council’s developing anti-racist approach. Changing names had to provide opportunities for public learning; to understand the legacy of the racist symbol and to celebrate Hackney’s African and African-Caribbean heritage in the public realm and through cultural programming such as Black History 365.

The review benefited from previous research carried out by Hackney Museum through projects such as the collaborative Legacies of Slave Ownership: Local Roots/Global Routes, in partnership with UCL history and Hackney Archives (2013-2015) and its exhibition output Who Were the Slave Owners of Hackney? And Hackney Museum’s exhibition African threads, Hackney Style (2015) which investigated 17th and 18th century City of London merchants and bankers with links to Hackney, and interconnected trades of cloth and enslaved people.

The review completed an audit of plaques, memorials, street and building names. Five names were identified and considered symbolic of racist histories. This was due to their connection to commerce that profited from the enslavement of Africans or imperial exploitation of African nations.

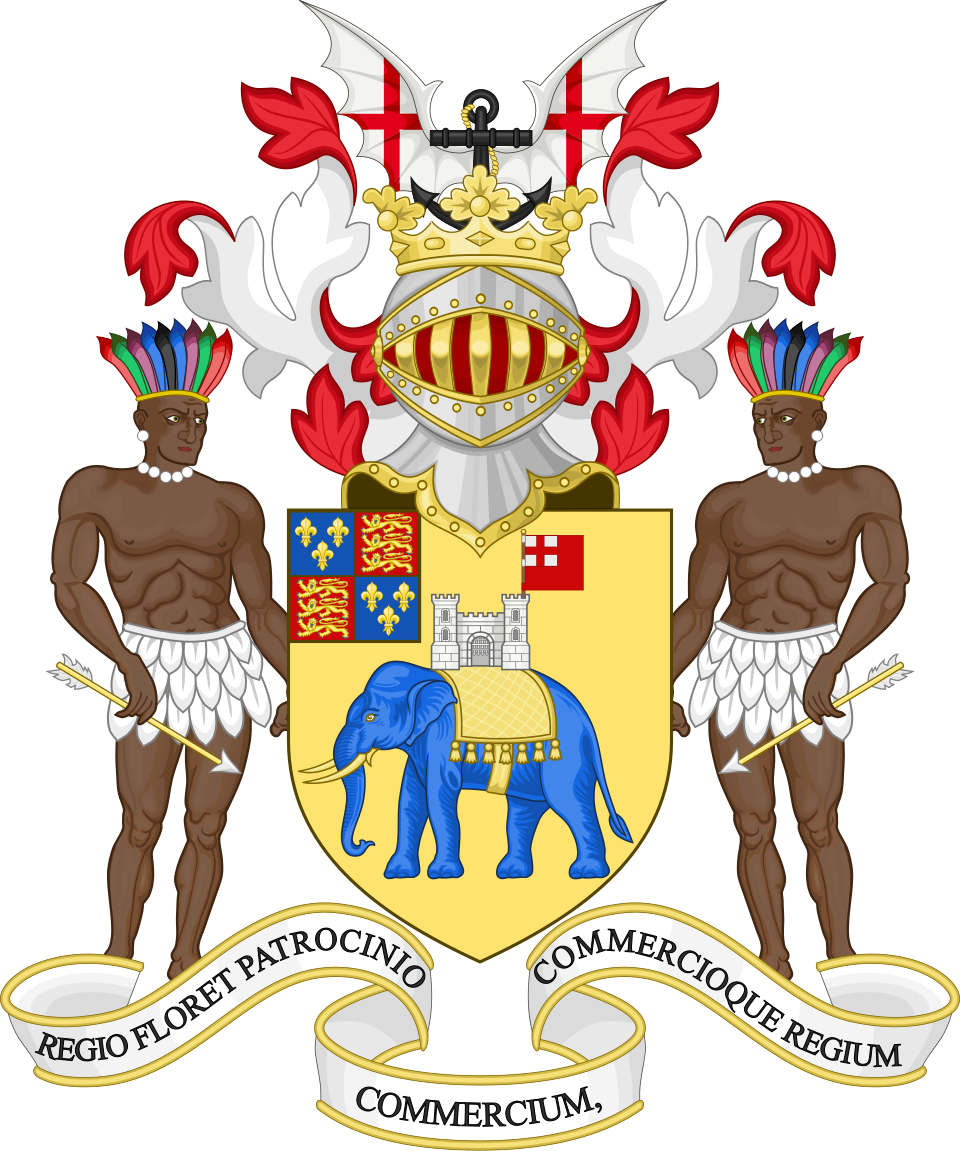

The Royal African Company (1660-1752) was established by The Stuart Royal Family and financed by merchant investors. Between 1662 and 1731, the RAC transported approximately 3,000 people per year (212,000 enslaved men, women and children) of whom 44,000 died en route to English colonies.

logo -CC BY-SA 4.0 0 caption

Contested figures

Sir Robert Aske (1619 to 1689)

A successful cloth merchant (Haberdasher) and investor in both the East India Company and the Royal African Company. With no heirs, his philanthropic bequest established the Aske Charity (linked to the Haberdashers Guild, in the City of London). The Aske Charity purchased land in Hoxton due to the stipulation that the hospital and school must be within one mile of the City of London.

ASKE remains present in Hackney’s public realm: Aske Street (N1); Aske House (N1).

Aske Gardens was renamed Joe White Gardens, 2023

Sir John Cass (1660-1719)

An investor in, and assistant (company director) of the Royal African Company. His philanthropic bequest established an education charity, which also benefited from his land portfolio in South Hackney. It was the charity, as the landowner, that later installed Cass’ name into the public realm during the rapid urbanisation of the mid-nineteenth century. The Sir John Cass Foundation was renamed The Portal Trust in 2021.

CASS remains present in Hackney’s public realm: Cassland Road (E9); Cass House on the Gascoigne Estate (E9).

In 2020 the name of Cassland Gardens was removed by Hackney Councillors and members of the community steering group. It was renamed Kit Crowley Gardens in 2021 after a public consultation.

The park sign was added to local museum collection [object number 2021.6] . This is expected to go on display in the new museum gallery, due to open in 2027.

An interpretation board was installed into the gardens explaining the name change from John Cass to Kit Crowley.

Sir Robert Geffrye (1613-1704)

An investor in, and assistant (company director) of the Royal African Company. With no heirs, Geffrye’s bequest built the Ironmongers almshouses in 1714, in Hoxton. The London County Council bought the property in 1911, which opened in 1924 as a museum with public garden to celebrate London’s furniture industry and craft, and provide some much needed green space.

There is a statue of Robert Geffrye on the museum’s Grade I listed building which acknowledges his donation to build the almshouse. Refer to the Museum of the Home for an update on the Robert Geffrye stature.

GEFFRYE remains present in Hackney’s public realm: Geffrye Estate (N1); Geffrye Court on the Geffrye Estate (N1), Geffrye Community Hall (N1); Geffrye Street (E2); Robert Geffrye Hall (N16).

Cecil John Rhodes (1835-1902)

Inherited a share of land in Dalston, Hackney, first purchased by his great grandfather. Due to Cecil’s wealth, generated through the exploitation of Africa’s natural resources (specifically diamonds), he was able to grow his Dalston estate by purchasing neighbouring land from his cousins. Rhodes is well documented in his imperialist actions and ideologies. His racist beliefs and political policies helped lay a system of apartheid in South Africa. This has left a troubling and enduring legacy of racism and inequality in southern Africa.

RHODES estate, Dalston was renamed in 2025.

Whilst the name RHODES does remain present in Hoxton (Rhodes House on the Provost Estate) this location has no direct link to Cecil Rhodes, but rather represents his ancestors who were farmers and brickmakers.

Francis Tyssen I (1624-1699)

An investor in the Royal African Company, East India Company with connections to American plantations that benefited from enslaved labour. He was also absentee plantation and slave owner on Caribbean island of Antigua. Several generations of the Tyssen family inherited the plantation and its enslaved workforce before selling the property in the early 19th century. The ancestors of the Tyssen family continue to hold the status of the Lord of the Manor of Hackney.

TYSSEN remains present in Hackney’s public realm: Tyssen Street (N1); Tyssen Road (N16); Tyssen Street (E8); Tyssen Passage (E8).

Tyssen Primary School was renamed Oldhill Community School & Children's Centre in 2021, with Councillor Bramble (left) and headteacher Jackie Benjamin (centre).